Local residential school artifacts to end up in national art project

A blanket is often seen as a symbol of comfort, but one First Nation artist’s project is bringing a much more complex meaning to it.

The project, called Witness Blanket, is a 30-foot long art installation. Artifacts from residential schools will be “woven” with wire over a large wooden frame.

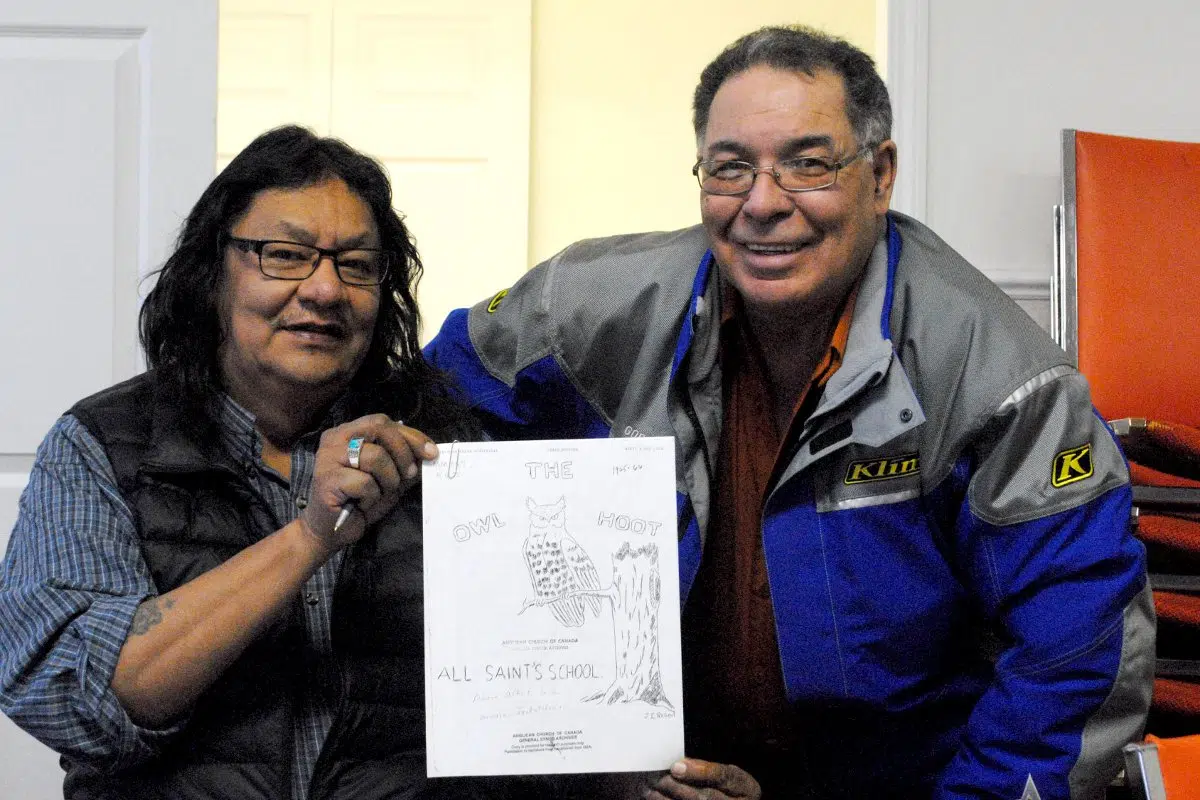

A Thursday trip to Prince Albert’s Indian Metis Friendship Centre was one of dozens across the country to collect the items.

The project was inspired by the concept of a woven blanket. British Columbian artist Carey Newman started it after he heard his father give a statement in his Indian residential school experience during a Truth and Reconciliation Commission meeting.

The items supplied vary widely. Some submissions are photos or books, others bricks, glass and wood from old schools. Even stories shared and written on paper will be included.